Wednesday, 30 December 2020

The Emerging Fellows Programme

Thursday, 24 December 2020

Is There A Gold Standard For Foresight?

Monday, 21 December 2020

The Terrible Twins (Again)

Monday, 14 December 2020

Does Foresight Provide Value?

Thursday, 10 December 2020

How Can We Distinguish Between Good Foresight And Poor Foresight?

Monday, 7 December 2020

Does Foresight Work?

Monday, 30 November 2020

Do Money Flows Uncover The Future?

Monday, 23 November 2020

The Belarussian Right Hook - Lessons Learned

Wednesday, 18 November 2020

The Belarussian Right Hook - The Timeline

Thursday, 12 November 2020

The Belarussian Right Hook - The Game

Wednesday, 28 October 2020

The Lure Of Nested Gaming

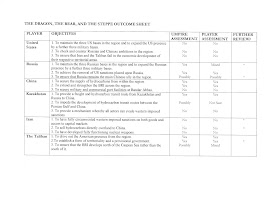

It often happens that, when gaming a series of future events, a game within a game presents itself. The most recent example was in our game 'The Dragon, The Bear, And The Steppe' (see here for more detail). This game contained a military engagement on the Caspian Sea and in south Turkmenistan between Russia, the US, and Kazakhstan on one side; and China and the Taliban on the other; with Iran intervening to act defensively. We dubbed this the 'Battle Of Turkmenbashi 2045' (see here for more detail).

Without going into the detail of how we would play the Battle of Turkmenbashi as a stand alone game, the whole concept of the game within a game set me thinking about the question of nested gaming. To begin with, ought we to confine ourselves to a single game within a game? Could there be more than one? In many ways, the idea of a succession of nested games within a game is the core of campaign gaming. A situation where a single event does not necessarily shape the eventual outcome, and where subsequent events can have a more decisive impact the other way. For example, the campaign in France in 1940 didn't settle the Second World War. From the Allied defeat came the basis for their eventual victory as fortunes eventually turned in favour of the Allies.

This, however, misses the flavour of nested gaming. What I am thinking of concerns the third - or even fourth - order events arising from the game. Take The Dragon, The Bear, And The Steppe as an example. That was the first order game. Within that game was the Battle of Turkmenbashi, as a second order game. Within The Dragon, The Bear, And The Steppe, the umpires determined, for example, the impact of events on the financial markets. What we could have done was to game the impact on the financial markets. This would have provided an interesting third order game. Gaming the reactions of market players could have provided an interesting set of fourth order games. This is an idea I find quite attractive.

One feature of nested games that seems apparent are the time scales involved. It seems to me that the lower the order of game, the shorter the time scale that is needed. For example, The Dragon, The Bear, And The Steppe was set over a time scale of 50 years. The second order game Battle of Turkmenbashi was set over a few days. To have built in these events as exogenous factors in a financial markets game would have represented hours rather than days. It is from here that my thoughts originate.

I would like to play a sequence of nested games. In my mind, we could have geopolitical events driving economic and financial events in two levels of gaming. Nested within that structure, we could then have a series of economic actors, such as Hedge Funds, looking to game, model, and profit from events as a third order game. Taking things further, we could even introduce a competitive element between the the players - or teams of players - in the third order game.

Thinking about where we could start, we have a number of games that could provide a number of quick and easy to play timelines for geopolitical events. For example, we have previously played games around the implosion of China (see here for an example) and the Russian invasion of the Baltic States (see here for an example). What we didn't do was to record in detail the timeline of events. That we can now do. The resulting timeline can then be used to input into a subsequent game examining the response of the financial markets to these geopolitical events. We do have one such game that could be taken off the shelf, updated, and given a new lease of life (see here for a description of the game).

Following on from that, with a timeline of geopolitical events and the associated policy responses from the financial markets, it ought to be relatively straightforward to devise a framework in which players can respond at the level of the individual firm. I think that ought to provide an interesting exercise. Hopefully we will be able to generate sufficient support to make it possible as an aspiration for 2021.

Stephen Aguilar-Millan© The European Futures Observatory 2020