|

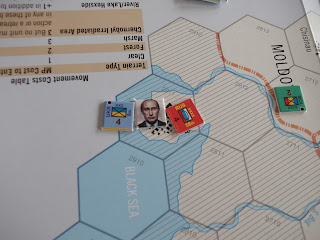

The Russian victory parade in Odessa.

|

We previously wrote about the game 'Putin's War', and how it might be pulled apart and reconstructed as a multi-player game which could be used to examine some of the issues affecting Russia's neighbours in the near future. We were recently given an opportunity progress this idea at a gaming conference.

One of the aspects of the vanilla game that sat awkwardly for us was the uniformity of the Blue team. To recap, the Blue team contained both Russia's neighbours (the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine), along with a selection of other nations within eastern Europe. We wanted to split this team into something that more closely resembled the current state of affairs.

In the vanilla game, the United States does not play a large part because of the logistics of sending a significant force to eastern Europe in a short space of time. We wanted to model this differently. We added a political game to the vanilla game that included the process by which Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty is invoked, adding delay upon delay before America could engage in operations. For the United States to become involved, Article 5 needs to be invoked, the North Atlantic Council needs to approve action, and Congress needs to ratify the decision for action. In a game modelling 30 days, the potential for delay is significant.

We didn't want to ignore recent developments in Europe either. As the United States appears to be lessening it's commitment to the defence of Europe, the European Commission is developing a Common Security and Defence Policy outside of the NATO structure. We wanted to give that a fair wind and to incorporate that idea into the game. The European arrangement organises member states into various battlegroups. We decided to use two such battlegroups - the Nordic Battlegroup (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, and Finland) and the Visegrad Battlegroup (Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic). The battlegroups would only be activated once the Common Security and Defence Policy is activated. This would come after the North Atlantic Council approved the invocation of Article 5, and required the approval of the European Council of Ministers.

As the United States appears to retreat from the defence of Europe, Germany naturally becomes more important in that defence infrastructure. Germany was represented by a single player, whose brief was to maintain the rating of the 10 Year Bund. We added a little financial aspect to the game, modelling the impact of conflict in eastern Europe on the bond market.

Two further key elements to the Blue team were Ukraine and Belarus. Not part of NATO, not part of the EU, already a victim of Russian aggression, Ukraine occupies a difficult position. We structured the game so that the Russian players could focus their attention on Ukraine without the direct intervention of NATO and the EU. We did try to encourage a little bit of Polish adventurism through the occupation of Ukrainian territory. Belarus, on the other hand, sat between the two sides. In reality, Belarus tries to maintain good links with both NATO and Russia. By assumption, we inserted a neutral Belarus into the game. We could equally have included Belarus in either the Blue team or, more realistically, the Red team. It would be interesting to run the same game three times, each with a different assumption about Belarus.

Although we talk of the Red team, this is actually Russia. We wanted to make Russia less monolithic, so we spilt the team into two - the Southern Military District and the Western Military District. Following current deployments, the intended focus of the Southern Military District would be Ukraine and the focus of the Western Military District would be the Baltic States. We gave the Red team players the opportunity to play co-operatively or competitively with each other. The mechanism for this was the allocation of action points and the allocation of reinforcements from the Central and Eastern Military Districts.

The briefing to players was:

The purpose of the game is to consider how

eastern Europe could look if the Russian Federation were to take military

action to restore a land buffer between itself and the European NATO nations. By assumption, the scene is set for

the spring of 2020. Europe has been through a series of acrimonious

negotiations over Brexit, with the various Member States arguing over the

post-Brexit landscape. President Macron has failed to re-vitalise France,

leaving Germany the undisputed dominant force in the EU. The people of Europe responded by voting heavily for Eurosceptic politicians in the European

elections of 2019. On the other side of the Atlantic, the US Presidential

elections are under way, with the incumbent polling well on an ‘America First And Only’ platform.

Meanwhile, there are reports of large troop movements in the Russian Federation

…

The game unfolded more or less as we expected it to. The Russian players acted co-operatively and decided to focus on the occupation of Ukraine. The reinforcements were allocated to the Southern Military District and the area of Significant Ethnic Russian Population in Ukraine was occupied in the first turn. In a single move, the state of Malorossiya came into being. There was little response from the Blue team. As Ukraine is not part of NATO, it cannot start the process of invoking Article 5, which also means that the Common Security and Defence Policy could not be invoked. In terms of the game, Ukraine acts alone.

That did beg the question that if this would prove so easy, why hasn't it happened already? I think that the answer to that question highlights the weaknesses of gaming as a technique to view the future. All sorts of assumptions were made in the game about the behaviour of the players (which were written into the rules) and other key nations who weren't players (China springs to mind here). These assumptions are worth teasing out. For example, what if the United States, outside of the framework of NATO, had armed and trained the Ukrainian forces, making them much more effective than originally thought? What if western sanctions had caused far more caution on the part of Russia? What if Russia feared the possibility of a more adventurous Chinese response in Central Asia? None of this was covered in the game, but in real life it has to be taken into account.

We allocated an hour and a half to the game. This wasn't long enough. During that time, we only managed to brief the players on the game mechanism, the political game, and the working aspects of the Bond Market. This left us time for just a single turn. It was a long turn, with quite a lot happening, but the action was confined to Ukraine. The non-Ukrainian Blue team players had little to do because the Red team players avoided the trap of involving NATO at an early stage. I quite liked this as a model of real action, but I accept that it didn't include the Blue team players as much as we had hoped that it might.

Looking to the future, I think that the experiment was sufficiently positive to continue with the game. We now know that it needs a good day to play through and that it has the potential to offer some useful insights into the near future history of eastern Europe. I believe that very few of the mechanisms need further tweaking, and that it would be good to roll it out over all of the ten turns to see how far it goes. All we need now is a group of willing volunteers and a venue.

Stephen Aguilar-Millan

© The European Futures Observatory 2017

No comments:

Post a Comment